Absence seizures also known as Petit Mal Seizures, characterized by brief episodes of impaired consciousness, are a type of generalized seizure that can significantly impact daily life, particularly in children and adolescents. Often subtle and mistaken for inattentiveness or daydreaming, these seizures require careful understanding for timely diagnosis and effective management. This article provides a comprehensive review of absence seizures, including their classification, prevalence, underlying mechanisms, clinical presentations in different age groups, diagnostic approaches, treatment strategies, and long-term outlook.

Understanding Absence Seizures: Typical vs. Atypical

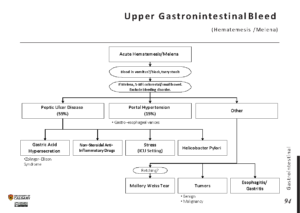

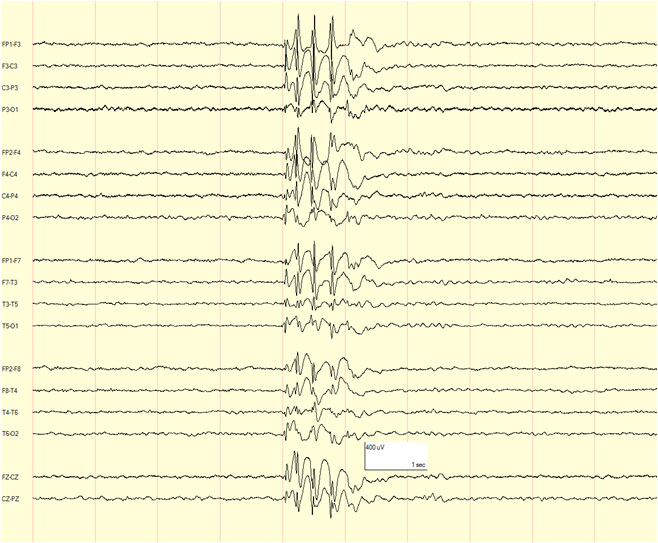

Absence seizures are broadly classified into two main categories: typical and atypical Absence seizures, which differ in their clinical presentation and electroencephalographic (EEG) findings.

Typical Absence Seizures: These are characterized by a sudden cessation of activity and a blank stare, usually lasting less than 20 seconds. Onset and termination are abrupt, with individuals typically resuming their previous activity immediately without postictal confusion. Subtle motor signs like rapid eye blinking or fluttering, upward eye turning, lip smacking, or minor hand movements may occur.

Atypical Absence Seizures: These seizures have a more gradual onset and termination, often lasting longer than typical absences (over 20 seconds). They are frequently associated with more pronounced changes in muscle tone, including loss of tone (atonic features), stiffening (tonic features), or jerking movements (myoclonic features). Atypical absence seizures are more common in individuals with other neurological problems or intellectual disabilities.

Epidemiology: Who is Affected by Absence Seizures?

Absence seizures are primarily a childhood phenomenon, with two main age-related syndromes: Childhood Absence Epilepsy (CAE) and Juvenile Absence Epilepsy (JAE).

Childhood Absence Epilepsy (CAE):

- Typically begins between 4 and 10 years of age, with a peak onset between 5 and 7 years.

- Accounts for 10% to 17% of all epilepsy cases in school-aged children, making it the most common form of pediatric epilepsy.

- More prevalent in girls than boys.

- Characterized by frequent seizures, often multiple times a day (10-50 or even hundreds).

- Often resolves spontaneously by adolescence, typically around age 12 or sooner.

Juvenile Absence Epilepsy (JAE):

- Onset typically occurs later, between 10 and 19 years of age, with a peak around 15 years, although it can start as early as 8 years old.

- Less common than CAE, accounting for 1% to 2% of childhood epilepsies and 2% to 3% of adult epilepsy cases.

- Sex distribution is more balanced or with a slight female predominance in some studies.

- Absence seizures are less frequent than in CAE, often occurring less than daily.

- Generalized tonic-clonic seizures are more common in JAE, occurring in about 80% of individuals.

- Less likely to remit spontaneously and often requires lifelong treatment.

The overall prevalence of absence seizures in the general population is estimated to be between 0.7 and 4.6 per 100,000 individuals.

Genetic Basis and Risk Factors

Absence seizures, particularly CAE and JAE, have a strong genetic component. Approximately 25% of children with absence seizures have a relative with the condition. The inheritance pattern is often multifactorial and polygenic. Several genes involved in ion channel function and neurotransmitter regulation have been implicated.

Certain factors can trigger absence seizures in susceptible individuals, including sleep deprivation, stress, and flashing lights (photosensitivity). Additionally, some anticonvulsant medications like phenytoin, carbamazepine, and vigabatrin may increase the risk of absence seizures.

Pathophysiology: What Happens in the Brain?

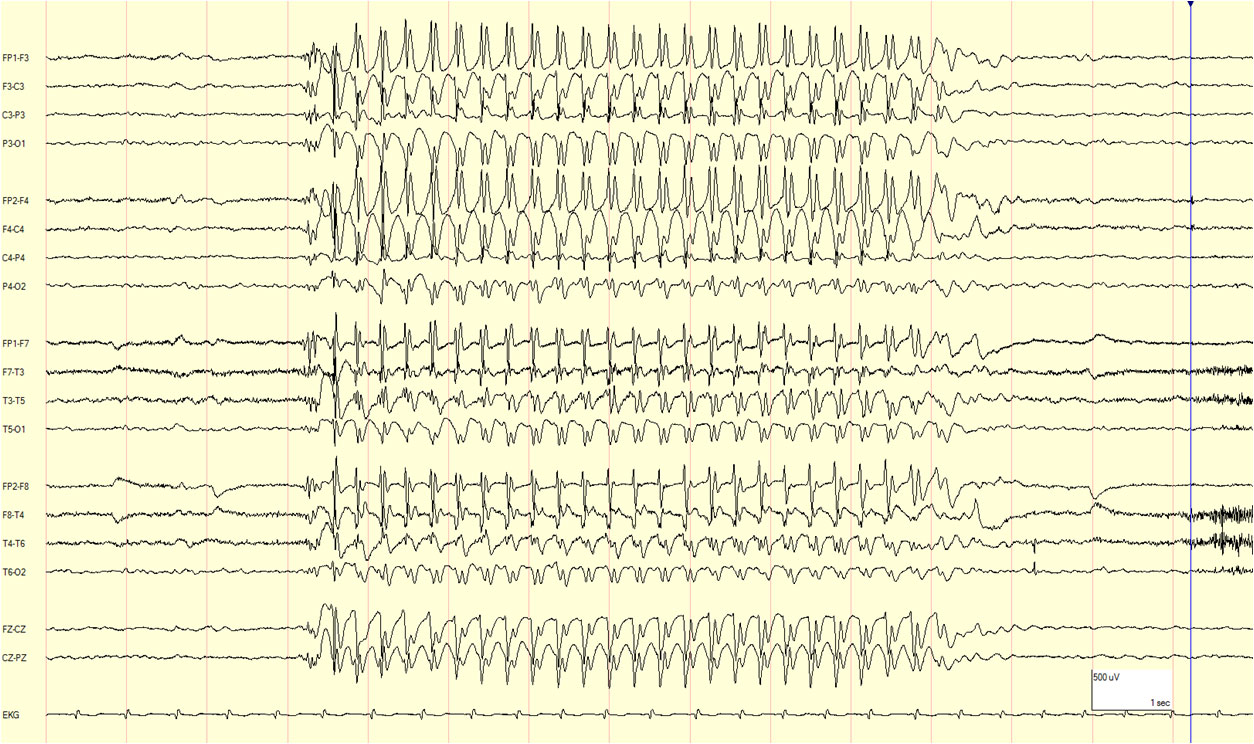

The underlying mechanism of absence seizures involves abnormal electrical activity within the cortico-thalamic-cortical (CTC) circuit. This circuit includes the cortex, thalamus, and their interconnections. Disruptions in the balance of excitatory (glutamate) and inhibitory (GABA) neurotransmission within this circuit are crucial in the generation of the characteristic spike-and-wave discharges seen on EEG during absence seizures. T-type calcium channels in thalamic neurons also play a significant role in the oscillatory activity associated with these seizures. Enhanced tonic GABA-A inhibition in thalamocortical neurons appears to be both necessary and sufficient for the generation of absence seizures.

Clinical Manifestations: Recognizing the Seizures

The hallmark of absence seizures is a sudden, brief lapse in awareness, often accompanied by a blank stare. This can be mistaken for daydreaming or inattentiveness. Key features include:

- Staring Spells: Sudden cessation of activity with a blank stare and unresponsiveness.

- Subtle Motor Movements: Eyelid fluttering or blinking, lip smacking, chewing motions, or slight jerking of limbs.

- Brief Duration: Typically lasting only a few seconds (usually less than 20 seconds in CAE, up to 45 seconds in JAE).

- Abrupt Onset and Termination: Seizures start and stop suddenly.

- Immediate Return to Normalcy: Individuals resume normal activity immediately after the seizure without confusion.

- Frequency: Can occur multiple times a day, especially in CAE.

In JAE, absence seizures may be less frequent but tend to last longer (10-45 seconds). Generalized tonic-clonic seizures are also common in JAE.

Diagnosis: Identifying Absence Seizures

Diagnosing absence seizures involves a combination of clinical evaluation and EEG findings.

- Medical History and Observation: Detailed information about the frequency, duration, and characteristics of the episodes is crucial. Witness accounts from parents, teachers, or caregivers are valuable.

- Electroencephalogram (EEG): This is the primary diagnostic tool, recording brain electrical activity. In typical absence seizures, the EEG often shows a characteristic pattern of generalized spike-and-wave discharges at 3 Hz (cycles per second) on a normal background. In JAE, the frequency may be slightly faster (3-4 Hz) and may include polyspikes.

- Activation Procedures: Hyperventilation (rapid and deep breathing) and photic stimulation (flashing lights) during EEG can often provoke absence seizures and characteristic EEG patterns.

- Video-EEG Monitoring: Simultaneous recording of EEG and behavior can be helpful in distinguishing epileptic seizures from other events.

- Neuroimaging (MRI): While often normal in typical CAE and JAE, MRI may be performed to rule out underlying structural abnormalities, especially in cases with atypical features or early onset. Advanced MRI techniques may identify subtle lesions in some cases.

Differential Diagnosis: Conditions Mimicking Absence Seizures

It is important to differentiate absence seizures from other conditions that can cause staring spells or inattentiveness. These include:

- Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD): Particularly the inattentive subtype, can present with staring and inattentiveness. However, attention can usually be regained in ADHD, unlike during an absence seizure.

- Daydreaming: Common in children and can be mistaken for absence seizures. Absence seizures occur suddenly and cannot be interrupted, while daydreaming usually comes on slowly and can be interrupted.

- Complex Partial Seizures: Can sometimes resemble absence seizures, especially if prolonged with automatisms. However, absence seizures typically have an abrupt end and lack a postictal phase.

Treatment Options: Managing Absence Seizures

While there is no cure for absence seizures, they can often be effectively managed with appropriate treatment. The goal is to reduce seizure frequency and severity.

Antiepileptic Medications (AEDs): These are the mainstay of treatment.

- Ethosuximide: Often the first-line medication for typical absence seizures in CAE due to its effectiveness and fewer attentional side effects.

- Valproic Acid: Effective for both absence and generalized tonic-clonic seizures, making it a common choice for both CAE and JAE. However, it may have more side effects, including attentional dysfunction.

- Lamotrigine: Can be used as an alternative, with some studies suggesting it may be less effective for absence seizures compared to ethosuximide or valproic acid but with fewer side effects.

- Other AEDs: Topiramate, zonisamide, levetiracetam, and clobazam may be used if first-line treatments are not effective.

- AEDs to Avoid: Carbamazepine, phenytoin, and vigabatrin can worsen absence seizures.

Ketogenic Diet: A high-fat, low-carbohydrate diet that can be effective in reducing seizure frequency, particularly in medication-resistant cases. It requires strict adherence and medical supervision.

Vagus Nerve Stimulation (VNS): May be considered for drug-resistant absence epilepsy syndromes. It involves implanting a device that sends electrical impulses to the brain via the vagus nerve.

Deep Brain Stimulation (DBS): While primarily studied for focal seizures, DBS targeting the centromedian nucleus of the thalamus has shown some efficacy in generalized epilepsies, including absence seizures.

Long-Term Prognosis and Impact on Quality of Life

The prognosis for absence seizures varies depending on the syndrome.

- CAE: Approximately two-thirds of children achieve seizure freedom by adolescence and may be able to discontinue medication. However, some may develop other seizure types. Factors like early onset, presence of other seizure types, and poor response to initial medication may indicate a less favorable prognosis.

- JAE: Generally considered a lifelong condition, but seizures are usually well-controlled with medication in most cases. Discontinuation of medication often leads to relapse. Some individuals with JAE may progress to juvenile myoclonic epilepsy.

Absence seizures can impact cognitive development, academic performance, and psychosocial well-being. Frequent seizures can interfere with learning and concentration. Children may experience social difficulties and emotional issues like anxiety and depression. Early diagnosis and appropriate management are crucial to minimize these potential long-term impacts.

Key Differences Between Childhood Absence Epilepsy (CAE) and Juvenile Absence Epilepsy (JAE)

| Feature | Childhood Absence Epilepsy (CAE) | Juvenile Absence Epilepsy (JAE) |

| Age of Onset | 4-10 years (peak 5-7 years) | 10-19 years (peak around 15 years) |

| Seizure Frequency | Frequent (multiple times daily) | Less frequent (less than daily) |

| Seizure Duration | Brief (usually less than 20 seconds) | Longer (10-45 seconds) |

| Tonic-Clonic Seizures | Less common (up to 40%) | More common (around 80%) |

| Remission | Likely to remit by adolescence (around age 12) | Less likely to remit spontaneously, often lifelong |

| Sex Predominance | More common in girls | More balanced or slight female predominance |

| Cognitive Impact | May have attention, concentration, and memory problems | May have attention, concentration, memory, and language problems |

| Prognosis | Generally good, often outgrown | Usually well-controlled with medication, but often lifelong |

Understanding the nuances of absence seizures, including their different types and associated syndromes, is essential for accurate diagnosis and tailored management. Early intervention and ongoing support can significantly improve the quality of life for individuals affected by this condition.

References

- Fisher, Robert S., et al. “ILAE Official Report: A Practical Clinical Definition of Epilepsy.” Epilepsia, vol. 55, no. 4, Wiley, Apr. 2014, pp. 475–82, https://doi.org/10.1111/epi.12550. Accessed 21 Mar. 2025.

- Moeller, Friederike, et al. “Absence Seizures: Individual Patterns Revealed by EEG‐FMRI.” Epilepsia, vol. 51, no. 10, Wiley, Aug. 2010, pp. 2000–10, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1528-1167.2010.02698.x. Accessed 30 Mar. 2025.

- Albuja, Ana C., et al. “Absence Seizure.” Nih.gov, StatPearls Publishing, 20 Apr. 2024, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK499867/. Accessed 23 Mar. 2025.

- Tenney, Jeffrey R., and Tracy A. Glauser. “The Current State of Absence Epilepsy: Can We Have Your Attention?” Epiliepsy Currents/Epilepsy Currents, vol. 13, no. 3, SAGE Publishing, May 2013, pp. 135–40, https://doi.org/10.5698/1535-7511-13.3.135. Accessed 24 Mar. 2025.

- Sisira Yadala, and Krishna Nalleballe. “Juvenile Absence Epilepsy.” Nih.gov, StatPearls Publishing, 7 Aug. 2023, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK559055/. Accessed 24 Mar. 2025.

- Alioth Guerrero-Aranda, et al. “Quantitative EEG Analysis in Typical Absence Seizures: Unveiling Spectral Dynamics and Entropy Patterns.” Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, vol. 17, Frontiers Media, Oct. 2023, https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2023.1274834. Accessed 25 Mar. 2025.

- Posner, Ewa. “Absence Seizures in Children.” BMJ Clinical Evidence, vol. 2008, Jan. 2008, p. 0317, pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC2907950/. Accessed 25 Mar. 2025.

- Operto, Francesca Felicia, et al. “Perampanel and Childhood Absence Epilepsy: A Real Life Experience.” Frontiers in Neurology, vol. 13, Frontiers Media, Aug. 2022, https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2022.952900. Accessed 25 Mar. 2025.

- Brigo, Francesco, et al. “Ethosuximide, Sodium Valproate or Lamotrigine for Absence Seizures in Children and Adolescents.” Cochrane Library, Elsevier BV, Feb. 2019, https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.cd003032.pub4. Accessed 26 Mar. 2025.

- Samo Gregorčič, et al. “Difficult to Treat Absence Seizures in Children: A Single-Center Retrospective Study.” Frontiers in Neurology, vol. 13, Frontiers Media, Sept. 2022, https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2022.958369. Accessed 26 Mar. 2025.

- Leitch, Beulah. “Molecular Mechanisms Underlying the Generation of Absence Seizures: Identification of Potential Targets for Therapeutic Intervention.” International Journal of Molecular Sciences, vol. 25, no. 18, MDPI AG, Sept. 2024, p. 9821, https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms25189821. Accessed 26 Mar. 2025.

- Kessler, Sudha Kilaru, and Emily McGinnis. “A Practical Guide to Treatment of Childhood Absence Epilepsy.” Pediatric Drugs, vol. 21, no. 1, Springer Science and Business Media LLC, Feb. 2019, pp. 15–24, https://doi.org/10.1007/s40272-019-00325-x. Accessed 27 Mar. 2025.

- Miray Atacan Yaşgüçlükal, et al. “Long-Term Prognosis of Childhood Absence Epilepsy.” Nöro Psikiyatri Arşivi, Jan. 2023, https://doi.org/10.29399/npa.28583. Accessed 27 Mar. 2025.

- Wirrell, E. C., et al. “Long-Term Prognosis of Typical Childhood Absence Epilepsy.” Neurology, vol. 47, no. 4, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Oct. 1996, pp. 912–18, https://doi.org/10.1212/wnl.47.4.912. Accessed 28 Mar. 2025.

- Amianto, Federico, et al. “Clinical and Instrumental Follow-up of Childhood Absence Epilepsy (CAE): Exploration of Prognostic Factors.” Children, vol. 9, no. 10, Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute, Sept. 2022, pp. 1452–52, https://doi.org/10.3390/children9101452. Accessed 28 Mar. 2025.

- Sadek, Joseph. “Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder Misdiagnosis: Why Medical Evaluation Should Be a Part of ADHD Assessment.” Brain Sciences, vol. 13, no. 11, MDPI AG, Oct. 2023, p. 1522, https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci13111522. Accessed 29 Mar. 2025.

- Pavone, P., et al. “Neuropsychological Assessment in Children with Absence Epilepsy.” Neurology, vol. 56, no. 8, Ovid Technologies (Wolters Kluwer Health), Apr. 2001, pp. 1047–51, https://doi.org/10.1212/wnl.56.8.1047. Accessed 30 Mar. 2025.

- Fonseca Wald, Eric L. A., et al. “Towards a Better Understanding of Cognitive Deficits in Absence Epilepsy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.” Neuropsychology Review, vol. 29, no. 4, Springer Science and Business Media LLC, Nov. 2019, pp. 421–49, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11065-019-09419-2. Accessed 30 Mar. 2025.