Frontotemporal Dementia, often abbreviated as FTD, is a group of disorders caused by progressive nerve cell loss in the brain’s frontal or temporal lobes. This condition is one of the less commonly known forms of dementia but is a significant cause of cognitive and behavioral changes, especially in younger individuals. Unlike other types of dementia, this condition primarily affects personality, behavior, and language abilities rather than memory in its early stages. In this article, we will explore the overview, symptoms, causes, and progression of Frontotemporal Dementia to provide a comprehensive understanding of this complex disorder.

What is Frontotemporal Dementia?

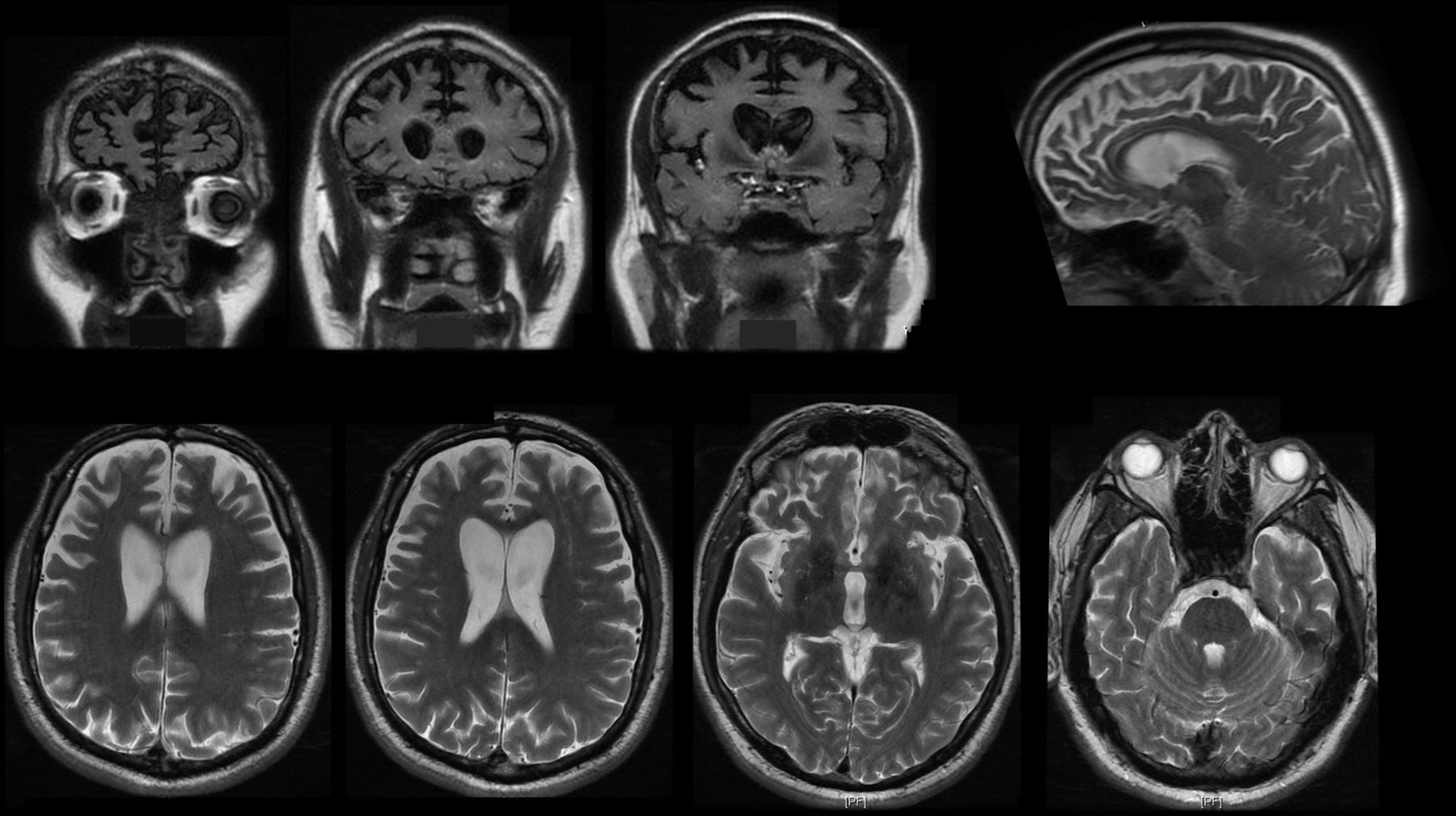

Frontotemporal Dementia refers to a spectrum of neurodegenerative disorders that primarily affect the frontal and temporal lobes of the brain. These areas are responsible for regulating behavior, personality, decision-making, and language. When these regions begin to deteriorate, individuals may experience profound changes in their ability to interact with others, manage emotions, and communicate effectively.

Unlike Alzheimer’s disease, which predominantly affects memory, Frontotemporal Dementia often spares memory in its early stages. Instead, it manifests through behavioral abnormalities and language difficulties. The onset of this condition typically occurs between the ages of 40 and 65, making it one of the most common causes of early-onset dementia.

Types of Frontotemporal Dementia

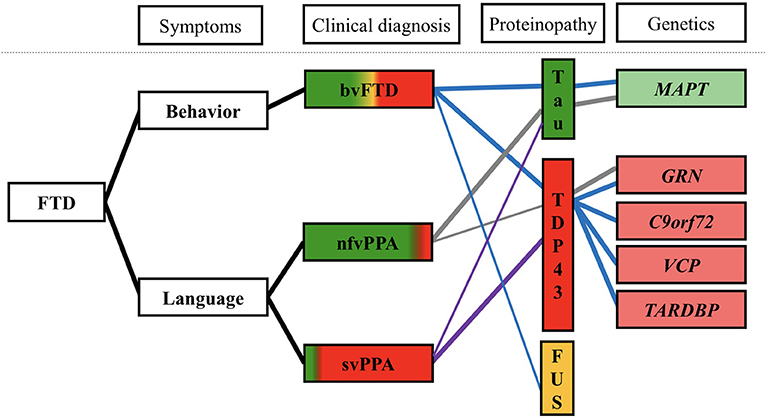

- Behavioral Variant Frontotemporal Dementia: This type is characterized by significant changes in personality and behavior. Individuals may exhibit socially inappropriate actions, apathy, or impulsivity.

- Primary Progressive Aphasia: This form primarily affects language abilities. It can be further divided into two subtypes:

- Semantic Variant: Difficulty understanding words and recognizing objects.

- Nonfluent/Agrammatic Variant: Challenges in forming sentences and speaking fluently.

- Movement Disorders: Some cases of Frontotemporal Dementia are associated with motor symptoms similar to Parkinson’s disease or Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis.

Symptoms of Frontotemporal Dementia

The symptoms of Frontotemporal Dementia vary depending on the specific subtype and the area of the brain affected. However, there are some common signs that may indicate the presence of this condition.

Behavioral Changes

Individuals with Frontotemporal Dementia often display noticeable changes in their behavior. These changes can include:

- Loss of empathy and diminished ability to understand others’ emotions.

- Inappropriate social behavior, such as making tactless comments or exhibiting impulsive actions.

- Apathy or lack of motivation, leading to withdrawal from social activities and responsibilities.

- Repetitive or compulsive behaviors, such as hoarding or adhering rigidly to routines.

Language Difficulties

Language impairment is a hallmark of certain subtypes of Frontotemporal Dementia. Common language-related symptoms include:

- Trouble finding the right words during conversations.

- Difficulty understanding spoken or written language.

- Challenges in constructing grammatically correct sentences.

- Progressive loss of vocabulary and comprehension of word meanings.

Cognitive Decline

While memory is not initially affected, individuals may experience cognitive impairments in other areas, such as:

- Poor judgment and decision-making abilities.

- Difficulty planning and organizing tasks.

- Problems with multitasking or focusing on complex activities.

Motor Symptoms

In some cases, Frontotemporal Dementia is accompanied by physical symptoms that resemble movement disorders. These may include:

- Muscle stiffness or weakness.

- Tremors or difficulty with coordination.

- Slowed movements or difficulty initiating actions.

Causes of Frontotemporal Dementia

The exact cause of Frontotemporal Dementia remains unknown in many cases. However, research has identified several factors that contribute to its development.

Genetic Factors

Approximately 30 to 50 percent of individuals with Frontotemporal Dementia have a family history of the condition. Mutations in specific genes, such as the C9orf72, GRN, and MAPT genes, have been linked to inherited forms of the disorder. These genetic mutations lead to abnormal protein accumulation in the brain, causing nerve cell damage and death.

Protein Abnormalities

Frontotemporal Dementia is associated with the buildup of abnormal proteins in the brain. Two primary types of protein aggregates are commonly observed:

- Tau proteins, which interfere with the structure and function of neurons.

- TDP-43 proteins, which disrupt cellular processes and contribute to nerve cell degeneration.

Environmental and Lifestyle Factors

While genetics play a significant role, environmental and lifestyle factors may also influence the risk of developing Frontotemporal Dementia. These factors include:

- Head injuries or trauma.

- Exposure to toxins or harmful substances.

- Chronic health conditions, such as diabetes or cardiovascular disease.

Progression of Frontotemporal Dementia

Frontotemporal Dementia is a progressive disorder, meaning that symptoms worsen over time. The rate of progression varies from person to person, but the condition typically advances in distinct stages.

Early Stage

In the early stage, individuals may notice subtle changes in behavior or language. These symptoms are often mistaken for personality quirks or stress-related issues. For example, a person might become more withdrawn, start making inappropriate comments, or struggle to find words during conversations. During this phase, daily functioning is usually preserved, although close friends and family members may observe concerning patterns.

Middle Stage

As the condition progresses to the middle stage, symptoms become more pronounced and disruptive. Behavioral changes intensify, leading to challenges in maintaining relationships and fulfilling responsibilities. Language difficulties worsen, making communication increasingly difficult. Individuals may require assistance with daily tasks, such as managing finances or preparing meals. Motor symptoms, if present, may also become more apparent during this stage.

Late Stage

In the late stage of Frontotemporal Dementia, individuals experience severe cognitive and physical decline. They may lose the ability to speak, recognize loved ones, or perform basic self-care activities. Full-time care is typically necessary to ensure safety and well-being. While memory loss becomes more prominent in this stage, the hallmark features of behavioral and language impairments remain central to the condition.

Diagnosis and Differential Diagnosis

Diagnosing Frontotemporal Dementia can be challenging due to its overlapping symptoms with other neurological and psychiatric conditions. A comprehensive evaluation is essential to rule out other potential causes and confirm the diagnosis.

Diagnostic Process

The diagnostic process typically involves:

- Clinical Assessment: A detailed medical history and neurological examination to evaluate cognitive and behavioral changes.

- Neuropsychological Testing: Assessments to measure cognitive functions, such as memory, language, and problem-solving abilities.

- Brain Imaging: Techniques like magnetic resonance imaging or positron emission tomography to identify structural or functional abnormalities in the brain.

- Genetic Testing: In cases with a family history, genetic testing may be recommended to identify mutations associated with Frontotemporal Dementia.

Differential Diagnosis

Several conditions can mimic the symptoms of Frontotemporal Dementia, including:

- Alzheimer’s disease.

- Psychiatric disorders, such as depression or bipolar disorder.

- Other neurodegenerative diseases, such as Parkinson’s disease or Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis.

Accurate diagnosis is crucial for developing an appropriate treatment plan and providing support to individuals and their families.

Treatment and Management

While there is currently no cure for Frontotemporal Dementia, various strategies can help manage symptoms and improve quality of life.

Medications

Certain medications may be prescribed to address specific symptoms:

- Antidepressants to manage mood changes or compulsive behaviors.

- Antipsychotics to reduce agitation or aggression.

- Speech therapy medications to support language abilities.

Therapies

Non-pharmacological approaches are also beneficial:

- Speech and language therapy to enhance communication skills.

- Occupational therapy to maintain independence in daily activities.

- Counseling or support groups for individuals and caregivers.

Lifestyle Modifications

Adopting healthy lifestyle practices can help slow symptom progression:

- Regular physical exercise to promote overall well-being.

- A balanced diet rich in antioxidants and nutrients.

- Engaging in mentally stimulating activities to preserve cognitive function.